Introduction

Cardio-cerebral infarction (CCI) is the occurrence of both acute ischemic stroke (AIS) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) at the same time (simultaneous or synchronous) or consecutively (metachronous). According to published literature, metachronous CCI occurs with an incidence of 0.9-12.7%1. In contrast, synchronous CCI (occurrence of AMI and AIS within 48 h) is extremely rare, with an incidence of 0.009%1,2. CCI presents a significant challenge to clinicians, as both AIS and AMI are medical emergencies requiring early diagnosis but with different treatment strategies1,2. We report a case of a 67-year-old patient presenting with AIS that occurred concurrently with AMI.

Case report

A 67-year-old male with a history of active smoking (on average, 10 cigarettes per day since the age of 15) presented to our unit with a sudden onset of dyspnea and persistent blurred vision. He reported experiencing intense chest pain 24 h before admission and blurry vision shortly after that; he denied hemiparesis, facial deviation, or altered mental status.

Upon physical examination, the patient presented with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15/15 (E4V5M6), heart rate of 83 beats/min, pallor, mild-dysarthria, cold limbs, and hypotension (80/50 mmHg); pulmonary crackles with a third and fourth heart sound were heard on auscultation.

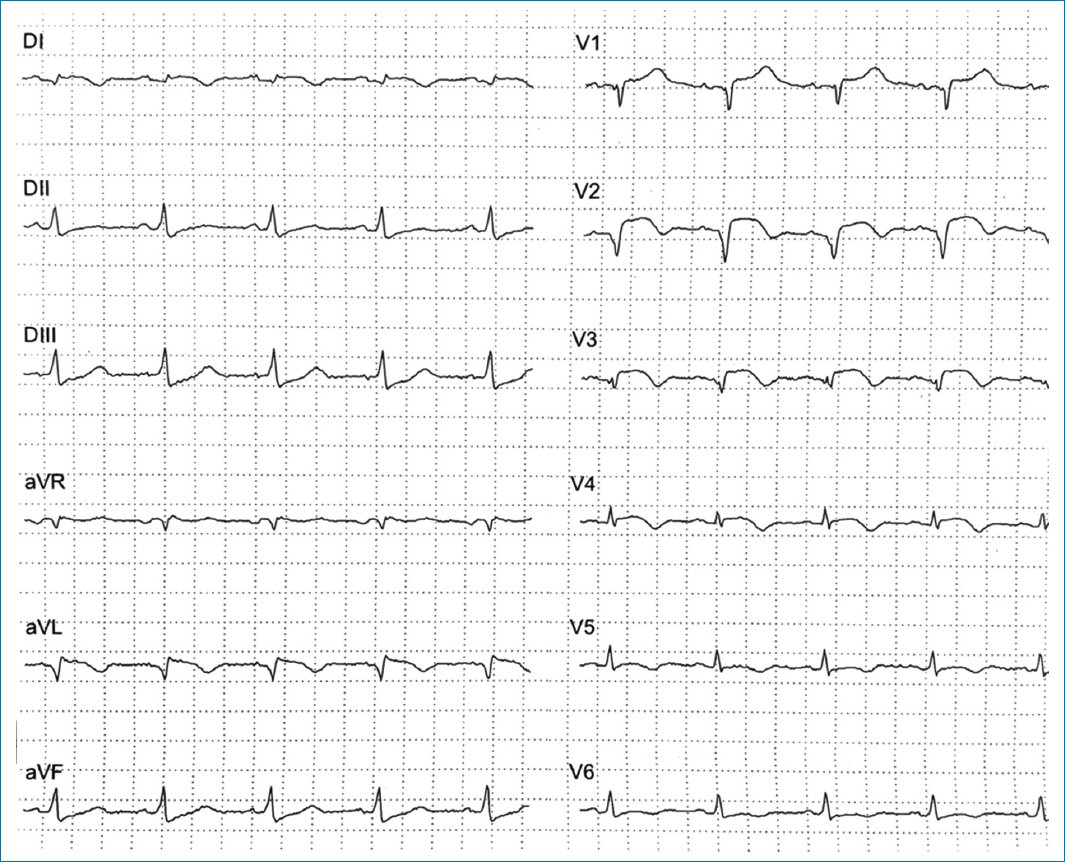

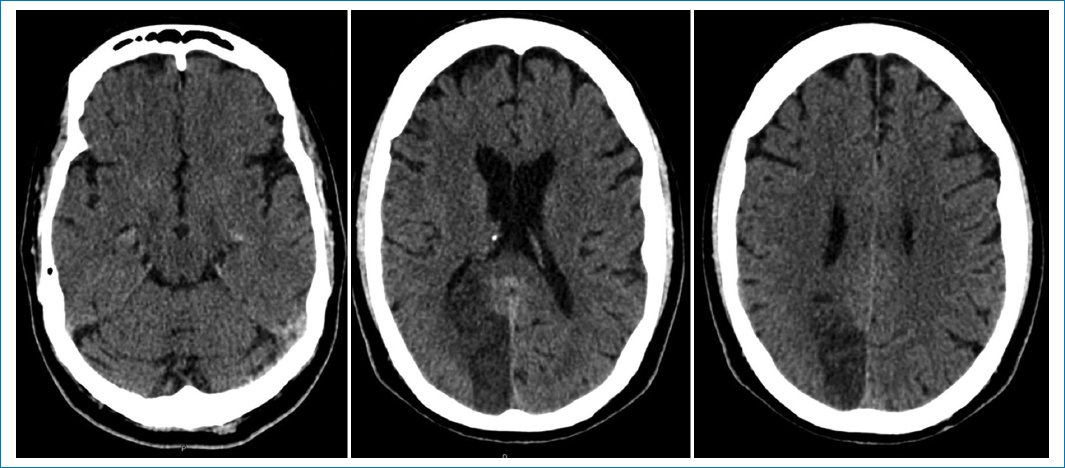

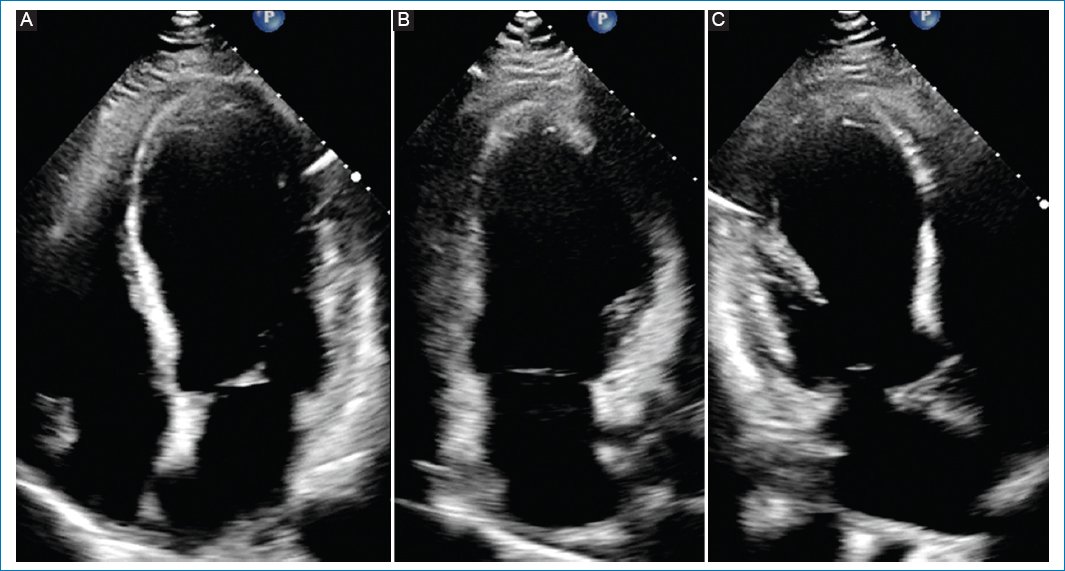

The electrocardiogram was relevant for persistent ST elevation on leads V2 and V3, T-wave inversion of leads DI, aVL, V2-V6, and Q-wave in leads DI, aVL, V1-V3, suggestive of an evolved anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (Fig. 1). The results of blood tests revealed high levels of troponin and brain-type natriuretic peptide (Table 1). The computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed an ischemic infarct in the posterior cerebral artery territory (Fig. 2). The transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed dyskinesia of the apical septal, mid-inferoseptal, apical anterior, and mid-anterior walls; hypokinesia in the basal inferoseptal, apical lateral, mid-anterolateral, and basal anterior walls; and akinesia in the apical inferior, anteroseptal, and apical lateral walls of the left ventricle. The patient had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 36%, no right ventricular systolic dysfunction, and no valvulopathies (Fig. 3).

Figure 1. Electrocardiogram showing lateral subepicardial ischemia with a non-reperfused anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction: T-wave inversion in leads DI, aVL, V1-V3, and persistent ST elevation in leads V2 and V3.

Table 1. Initial blood tests

| Test | Value | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes, mm3 | 8,930 | 5,000-10,000 |

| Platelets, mm3 | 287,000 | 130,000-400,000 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 15 | 14-18 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 135 | 135-145 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.4 | 3.5-5.1 |

| Chlorine, mEq/L | 100 | 98-107 |

| Phosphorus, mg/dL | 3.8 | 3.7-7.2 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 8.7 | 8.6-10.3 |

| Magnesium, mg/dL | 2.1 | 1.8-2.7 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 93 | 74-106 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 | 0.7-1.3 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 29 | 18-50 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 14 | 7.2-25 |

| Troponin, ng/mL | 2923 | < 19 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 93 | < 150 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 107 | < 200 |

| N-terminal proBNP, pg/mL | 5320 | < 125 |

|

BNP: brain-type natriuretic peptide. |

||

Figure 2. Non-contrast computed tomography showing a posterior cerebral artery infarct.

Figure 3. Transthoracic echocardiogram showing wall-motion abnormalities. A: apical four-chamber view: apical septal with mid inferoseptal dyskinesia, basal inferoseptal hypokinesia, and apical lateral with mid anterolateral hypokinesia. B: apical two-chamber view: apical inferior akinesia, apical anterior with mid anterior dyskinesia, and basal anterior hypokinesia. C: apical three-chamber view: anteroseptal and apical lateral akinesia.

The Stroke Team was consulted, and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was calculated to be 3 points, considering the patient was not a candidate for thrombolysis or thrombectomy since the therapeutic window time was over, and preferred prioritizing the management of cardiogenic shock (CS).

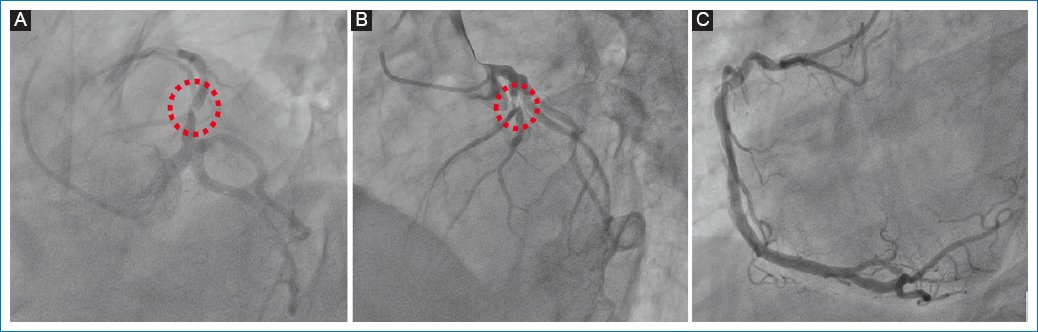

CS was treated pharmacologically with dual antiplatelets, atorvastatin, and noradrenaline paired with levosimendan (intravenous [IV] continuous infusion of 0.2 μg/kg/min for 24 h). A coronary angiography was immediately performed, revealing left anterior descending artery (LAD) lesions, and stents were implanted successfully (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Coronary angiography. A and B: involvement of the left anterior descending artery (red dotted line); C: right coronary artery without obstructive lesions.

Within 3 days, the patient recovered completely from CS, and the hospital stay was uneventful, with no arrhythmias recorded. The patient was finally discharged on day 7, symptom-free, with antiplatelet therapy and medication for heart failure (bisoprolol 5 mg SID, sacubitril/valsartan 50 mg BID, spironolactone 25 mg SID, and dapagliflozin 10 mg SID). Six-month follow-up showed improved vision, whereas TTE revealed an improved LVEF (45%).

Discussion

In stroke registries, 1% of patients with transient ischemic attacks or AIS and 0.3% of patients with hemorrhagic stroke suffered from AMI during treatment. Among patients suffering from AIS, 13.7% had elevated cardiac troponin levels. Likewise, stroke occurred in approximately 0.9% following an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), with the highest rates occurring in patients with STEMI. The risk of AIS increases within 5 days following an AMI3.

Simultaneous CCI, a term first described by Omar et al. in 2010, can be diagnosed by the presence of simultaneous acute onset of a focal neurological deficit, indicating AIS, and chest pain or evidence of AMI, such as changes of the electrocardiogram and the elevation of cardiac enzymes3–5.

The majority of patients with CCI are males (65.9%), and hypertension (31.8-78%), diabetes (15.9-56%), and smoking history (22-27.3%) are the most prevalent cardiovascular risk factors. Sixty-six percent of the patients arrived at the emergency department within 6 hours after the onset of AIS. According to the NIHSS score, 75% of the patients had moderate or moderate-to- severe strokes, and 69.6% had large vessel occlusions by brain imaging, predominantly affecting anterior cerebral circulation (56%) and posterior circulation (33.3%)1,6.

AMI is most associated with ST-elevation (56-78.6%) with occlusion of the LAD (68.8%), followed by right coronary vessels (31.3%). The main findings of the echocardiogram are an LVEF < 50% (38-83.3%) and regional wall motion abnormalities (50-74.1%)1,6. In this case, the patient had a history of active smoking and presented to the emergency department with anterior-wall STEMI and mild AIS affecting the posterior cerebral circulation 24 h after the onset of symptoms. Echocardiography showed low LVEF with wall motion abnormalities according to the LAD territory.

Approximately one-half of the patients exhibited neurologic deficits, followed by chest pain or dyspnea (53.2%). 19.1% of patients first developed symptoms of AMI, followed by symptoms of AIS. In 27.7% of cases, AMI and AIS symptoms co-occurred7. In our case, the patient experienced chest pain and neurological symptoms simultaneously; the development of CS caused dyspnea and hypotension.

Mortality rates range between 22.7% and 33%, and CS occurs in 9.1-33% of cases. In most cases, patients died from cardiac causes, including ventricular tachyarrhythmias, cardiac tamponade, aortic dissection, ventricular septal rupture, or sudden death1,6,7.

According to the most widely accepted hypotheses, simultaneous CCI is caused by three mechanisms7–9:

- – Concomitant thrombosis of the coronary and cerebral arteries, such as atrial fibrillation (AF), Type I aortic dissection involving the coronary artery and common carotid artery, or electrical injury leading to coronary and cerebral artery spasms.

- − Strokes caused by cardiac disease, such as intraventricular thrombosis, patent foramen ovale (complicated with right heart infarction), and CS after AMI.

- − A cerebral-cardiac axis disorder or cerebral infarction can lead to myocardial injury. The insular cortex, a crucial component of the central autonomic nervous system, is related to AF, cardiac sympathetic nerve activation, myocardial injury, and interruption of the circadian rhythm of blood pressure (BP).

An AMI, mainly if it occurs in the anterior wall or apex of the heart, weakens left ventricular systolic function, providing the pathophysiological basis for forming a left ventricular mural thrombus. Underpowered left ventricles are more susceptible to thrombosis, which can embolize the coronary and cerebral arteries. Consequently, severe hypotension can cause hemodynamic stroke. When automatic BP regulation fails in patients with AMI and a long history of hypertension, sudden hemodynamic compromise may result in a decrease in cerebral blood flow, resulting in AIS3,8.

Regarding incidence, outcome, and mechanism, posterior circulation stroke differs from anterior-circulation stroke. As an example, atherothrombosis is more prevalent (32%) in the posterior circulation as an underlying stroke cause than cardioembolism (18%). In contrast to patients with large artery atherosclerosis, patients with cardioembolism have better outcomes, better functional outcomes, a lower risk of death at 90 days, and the lowest NIHSS10. Therefore, considering the clinical picture, brain imaging, and neurological outcomes, we concluded that stroke was caused by the anterior STEMI that conditioned the severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction leading to left ventricular mural thrombus that embolized to the posterior cerebral artery circulation and subsequent CS associated with hemodynamic compromises further reduced cerebral blood flow, perpetuating cerebral ischemia.

Due to the rarity and complexity of the condition, there are presently few guidelines or recommendations for its diagnosis and treatment. Due to this, the treatment of CCI is very individual and does not follow a standard procedure7,11. In addition, the lack of an organized prehospital transfer system and the heavy traffic leading to the hospital may have contributed to delays in most patients arriving past the time window for IV reperfusion1. The interventional cardiology department and Stroke Team are critically important in determining the mode and sequence of revascularization before the patient is outside the therapeutic time window for intervention2.

Although fibrinolytic therapy with IV alteplase can be used in both AIS and acute STEMI, fibrinolytic therapy’s different dose requirements and timing after onset hinder its use as a definitive treatment for both conditions3.

According to the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines for the early management of AIS, for patients with concurrent AIS and AMI, an IV alteplase dose appropriate to the cerebral ischemia is reasonable, followed by percutaneous coronary angioplasty and stenting, if necessary (Class IIa, level of evidence C)12. For patients with AIS of < 4.5 hours duration and with a history of subacute (> 6 h) STEMI during the last 7 days, IV thrombolysis should not be administered to prevent complications (Evidence: Low, Recommendation: Weak)13.

A higher dose and a longer infusion time of fibrinolytic agents for STEMI, in comparison with a standard dose for AIS, may increase the risk of hemorrhagic transformation in patients with simultaneous CCI3,14,15.

In addition to being the agent of choice for fibrinolytic therapy in patients with AMI, there is an increased openness to using tenecteplase in patients with AIS. Notably, it was examined for its potential use in stroke because it can be administered intravenously in a single bolus rather than an hour-long infusion, which is less time-consuming in an emergency and may contribute to quicker door-to-needle times. The 0.10-0.40 mg/kg doses were found to have a more advantageous safety profile after several trials in AIS patients testing doses ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 mg/kg (maximum bolus dose of 10-50 mg)15.

In patients with AIS < 4.5 hours duration, administration of tenecteplase (TNK) 0.25 mg/kg can be used as a safe and effective alternative to alteplase (Evidence: Moderate, Recommendation: Strong), although a higher dose (0.40 mg/kg) should not be used for stroke treatment (Evidence: Low, Recommendation: Strong)15.

As a result of the STREAM-1 trial, it was discovered that patients 75 years of age or older with a ≤ 3 hours STEMI were at greater risk for intracranial bleeding when fibrinolysis was administered. Consequently, the dosage of TNK was decreased for these patients, showing effective reperfusion and an acceptable safety profile at 30 days and 1 year, and these findings were subsequently incorporated into guidelines for the management of STEMI14,16,17.

In the EARLY-MYO trial, half-dose alteplase (8 mg bolus followed by 42 mg in 90 min) was administered to patients with a STEMI within 6 hours and showed improved epicardial and myocardial perfusion and a low rate of major bleeding events (≤ 0.6%)18.

Subsequently, in the STREAM-2 trial, half-dose TNK was evaluated in patients ≥ 60 years and weighing ≥ 55 kg with a ≤ 3 hours STEMI and reported effective reperfusion with a low incidence of bleeding complications at 30 days (0.5-1.5%)19.

In light of these findings and pending further studies, evaluation, and inclusion in guidelines, we believe that TNK administration at half dose (0.25 mg/kg) may be an effective treatment option for individuals ≥ 75-years-old with hyperacute simultaneous CCI.

In case of suspected hyperacute simultaneous CCI (patients arriving within 4.5 hours of the thrombolytic therapeutic window), a CT brain, CT angiogram, CT perfusion, and electrocardiogram should be performed after initial evaluation to confirm the diagnosis. Following a re-evaluation of the hemodynamic status, further action is taken. A patient who has an unstable hemodynamic status or STEMI must undergo emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), followed by endovascular treatment for ischemic stroke if there is a large vessel occlusion. Those patients with stable hemodynamics should receive an IV dose of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. In cases of large vessel occlusion, endovascular treatment is then performed. Since right-middle cerebral artery infarction usually involves the right insular cortex, which is associated with increased mortality, it is recommended that these patients with hyperacute simultaneous CCI undergo close observation and cardiac monitoring for arrhythmias. In patients with non-ST-elevation-ACS, PCI may be performed according to two treatment strategies: ischemic-guided or early invasive therapy3. This case involved a patient who arrived late in the hospital after the optimal therapeutic window, which is essential for managing hyperacute simultaneous CCI and leading to better neurologic and cardiologic recovery. As a result of unstable hemodynamics and STEMI, urgent PCI and CS treatment were prioritized with excellent results.

Conclusion

Simultaneous CCI is a rare and devastating condition that is difficult to manage and has a high mortality and morbidity rates. Clinical suspicion is necessary to identify patients with CCI whose outcomes can be significantly affected by timely treatment. This condition requires additional clinical trials to establish the optimal management strategy.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

Protection of humans and animals. The authors declare that no experiments involving humans or animals were conducted for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The authors have followed their institution’s confidentiality protocols, obtained informed consent from patients, and received approval from the Ethics Committee. The SAGER guidelines were followed according to the nature of the study.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that no generative artificial intelligence was used in the writing of this manuscript.