Introduction

Benign pathologies of the biliary tract represent one of the most common problems in developed countries. Gallstone disease is observed in 10-15% of the Caucasian adult population1. Choledocholithiasis is defined as the presence of gallstones in the CBD or the common hepatic duct. Between 10 and 20% of patients with symptomatic gallstone disease may present with concomitant coledocolithiasis2,3, being present in up to 15% of all laparoscopic cholecystectomies performed annually4.

Acute calculous cholecystitis (ACC) is an acute infectious and inflammatory process that mainly involves the gallbladder wall due to a gallstone impacted in the infundibulum or cystic duct. ACC accounts for one-third of all surgical emergency admissions in hospitals and is the second leading cause of complicated intra-abdominal infection, according to the World Society of Emergency Surgery5.

Acute calculous cholecystitis (ACC) is the most common complication of gallstone disease and accounts for 14-30% of all cholecystectomies performed6. Moreover, the prevalence of choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC ranges from 7 to 20%, so the presence of choledocholithiasis should be investigated in all cases7.

Liver function tests (LFTs) are enzymes and metabolites sensitive to liver damage and, for many years, have been used as biochemical markers of liver function8. It is common for biliary tract obstruction to be accompanied by elevated LFTs as a result of increased pressure in the biliary tract, the permeability of the hepatocellular membrane, and hepatocellular toxicity of retained bile acids9,10.

The guidelines on “the role of endoscopy for the evaluation and management of choledocholithiasis” by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy incorporate values above 1.8 mg/dL, 60 U/L, and 100 U/L for total bilirubin (TB), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), respectively, as predictors of “intermediate” probability of choledocholithiasis, a category that provides a probability of 10-50% of finding stones in the CBD. These patients require some specialized study of the biliary tract, such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), intraoperative cholangiography (IOC), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), or laparoscopic ultrasound, to rule out the presence of choledocholithiasis. On the other hand, the combination of TB > 4 mg/dL and a dilated CBD (greater than 6 mm on a transverse imaging study or abdominal ultrasound) constitutes a “high” probability of choledocholithiasis, representing more than a 50% chance of finding stones in the main biliary tract. In these cases, one can proceed directly to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with a favorable risk-benefit ratio. At last, the absence of risk predictors or abnormalities in LFTs indicates a “low” probability of choledocholithiasis and patients in whom cholecystectomy can be performed with or without imaging studies of the biliary tract with a risk of less than 10% of choledocholithiasis3.

Normally, acute inflammation of the gallbladder is not accompanied by an elevation in LFTs; however, alterations in the LFTs are frequently found even in the absence of choledocholithiasis. One of the mechanisms attributable to abnormal elevation of LFTs during the acute process is the alteration of normal bile flow to its reservoir, which induces transient hepatocellular injury consequent to bacterial contamination and retrograde bile flow11. Additionally, the central and hepatic circulation of proinflammatory cytokines, endotoxins, and bacterial lipopolysaccharides, such as TNF-α, interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8, contribute to liver damage by activating the immune response and subsequent elevation of liver enzymes12.

Nowadays, there are many limitations to the routine use of specialized biliary tract imaging studies in Mexico. Their high cost and limited availability make it hard for the routine use of MRCP. ERCP requires the availability of radiology equipment in the operating room. Similar situations occur with EUS and laparoscopic ultrasound, where resource availability plays a decisive role. Therefore, having better cut-off points of LFTs as a screening tool for choledocholithiasis in laparoscopic cholecystectomy would benefit in reducing the need for specialized biliary tract imaging studies and generate substantial savings for the patient and health institutions.

The objective of this study is to describe the tendencies of LFTs and their practicality in detecting choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC, as well as to identify appropriate cut-off points to avoid specialized biliary tract imaging studies with the intention of reducing costs and intrahospital stays in hospital centers that do not have these resources.

Materials and/or methods

A descriptive, observational, longitudinal, retrospective, and analytical study was carried out through the review of clinical records of patients over 18 years of age with laparoscopic cholecystectomy with at least one alteration in LFTs preoperatively and a specialized biliary tract imaging study for the detection of choledocholithiasis at the ABC Medical Center in Mexico City, Mexico. Patients with a history of cholecystectomy, ERCP or previous intervention of the biliary tract, patients with stenosis or lesions of the biliary tract, and those with a diagnosis or suspicion of malignant neoplasm of the biliary tract were excluded. Patients with acute or chronic liver disease that could alter LFTs, as well as those with incomplete medical records that made data collection difficult, were also excluded.

With evidence that at least 10% of patients with symptomatic gallstones have concomitant choledocholithiasis, the sample size was calculated using a proportion for an infinite population with a 95% confidence interval, plus an additional 20% of patients for possible missing data, obtaining a representative sample of 166 patients. The independent quantitative variables studied were age, duration of symptoms, LFTs as TB, DB, indirect bilirubin (IB), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), ALP, and GGT and CBD diameter on ultrasound, while sex was the qualitative variable. The dependent variable was the presence of choledocholithiasis, as a dichotomous qualitative variable, according to the result of the specialized biliary tract imaging study used (MRCP, IOC, and/or ERCP). Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 21 statistical package. The distribution of continuous quantitative variables (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) was evaluated to observe the association with the presence of choledocholithiasis through parametric tests (student’s t-test for normal distribution) and non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U-test for free distribution), while the association analysis between qualitative variables was performed with the Pearson Chi-squared test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Normally distributed variables were described as means with standard deviation (SD) and free-distribution variables as median with interquartile range 25 and 75% (Q1-Q3).

A multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate the OR and 95% CIs to determine the effect of independent variables on the dependent variable. An OR > 1.00 was considered a risk factor, while < 1.00 was considered a protective factor. Optimal cut-off points were established for statistically significant continuous variables with respect to the dependent variable through the construction of ROC curves using the Youden index. Continuous variables were dichotomized with respect to the optimal cut-off point to create 2 × 2 tables, from which SE, SP, PPV, and negative predictive value (NPV) were obtained with respect to the presence of choledocholithiasis.

Results

A total of 166 consecutive clinical records of patients with ACC stones and at least one abnormality in LFTs were retrospectively collected from April 2022 to June 2019 (34 months) until the sample size was completed. Of these, 58% (n = 97) were men, and the rest were women, with a median age of 59 years (44-73). The prevalence of choledocholithiasis was 12% (n = 20). In the bivariate analysis, there was a significant relationship between the values of TB, DB, AST, ALT, ALP, GGT, and CBD diameter with respect to the presence of choledocholithiasis (p < 0.05) (Table 1), while there was no significant relationship between sex, age, duration of symptoms, and IB (p > 0.05). TB was excluded from further analysis due to collinearity.

Table 1. Independent variables regarding the presence of choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC and pre-surgical abnormalities LFTs

| Variable | Total | Choledocholithiasis | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| 166 (100%) | 146 (88%) | 20 (12%) | ||

| Men | 97 (58.4%) | 85 (58.2%) | 12 (60%) | 0.880 |

| Women | 69 (41.6%) | 61 (41.8%) | 8 (40%) | |

| Age (years)** | 59 (44-73) | 59 (44-72) | 59 (48-80) | 0.500 |

| Evolution time (days)** | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | 3 (1-6) | 0.414 |

| TB** | 1.25 (0.73-2.09) | 1.10 (0.68-1.73) | 2.76 (1.73-5.51) | < 0.001 |

| DB** | 0.53 (0.27-1.11) | 0.46 (0.24-0.82) | 1.98 (1.27-4.22) | < 0.001 |

| IB** | 0.54 (0.31-1.00) | 0.52 (0.31-0.93) | 0.74 (0.26-1.56) | 0.219 |

| AST** | 40 (19-101) | 35 (17-89) | 95 (44-197) | 0.001 |

| ALT** | 52 (22-125) | 49 (21-121) | 108 (53-192) | 0.016 |

| ALP** | 112 (81-169) | 109 (78-146) | 207 (101-333) | < 0.001 |

| GGT** | 115 (47-236) | 102 (41-218) | 218 (159-519) | 0.001 |

| CBD diameter (mm)** | 4.8 (3.5-6.0) | 4.5 (3.5-5.1) | 8.4 (5.5-10.5) | < 0.001 |

|

p: Pearson’s χ2 test (for dichotomous variables); Student’s t-test (for normally distributed quantitative variables); Mann-Whitney U test (for free distribution quantitative variables); significance level is p < 0.05; *mean (±SD); **median (Q1-Q3); AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; DB: direct bilirubin; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; IB: indirect bilirubin; TB: total bilirubin. |

||||

In the multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of the different LFTs, there was a statistically significant causal relationship between elevated DB (p < 0.001, OR = 2.6, 95% CI: 1.65-4.28) and ALP (p = 0.009, OR = 1.006, 95% CI: 1.002-1.011) and the presence of choledocholithiasis (Table 2). However, when CBD diameter was added to the equation, both elevated DB (p < 0.001, OR = 2.40, 95% CI: 1.48-3.89) and CBD diameter (p < 0.001, OR = 1.87, 95%

CI: 1.35-2.5) were statistically significant risk factors for the presence of choledocholithiasis (Table 3).

Table 2. Multivariate logistic regression of LFTs regarding the presence of choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC

| Variable | p | OR | IC 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| DB | < 0.001 | 2.667 | 1.659 | 4.288 |

| AST | 0.373 | 1.002 | 0.998 | 1.005 |

| ALT | 0.363 | 0.998 | 0.995 | 1.002 |

| ALP | 0.009 | 1.006 | 1.002 | 1.011 |

| GGT | 0.434 | 0.999 | 0.996 | 1.002 |

|

Variables in the equation: DB, AST, ALT, ALP, GGT; predicted percentage: 89.8%; the significance level is p < 0.05; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; DB: direct bilirubin; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase. |

||||

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression between LFTs and CBD diameter regarding the presence of choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC

| Variable | p | OR | IC 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| DB | < 0.001 | 2.407 | 1.488 | 3.895 |

| ALP | 0.057 | 1.005 | 1.000 | 1.010 |

| CBD diameter | < 0.001 | 1.876 | 1.358 | 2.591 |

|

Variables in the equation: DB, ALP, CBD diameter (mm); predicted percentage: 94.6%; the significance level is p < 0.05; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; CBD: common bile duct; DB: direct bilirubin. |

||||

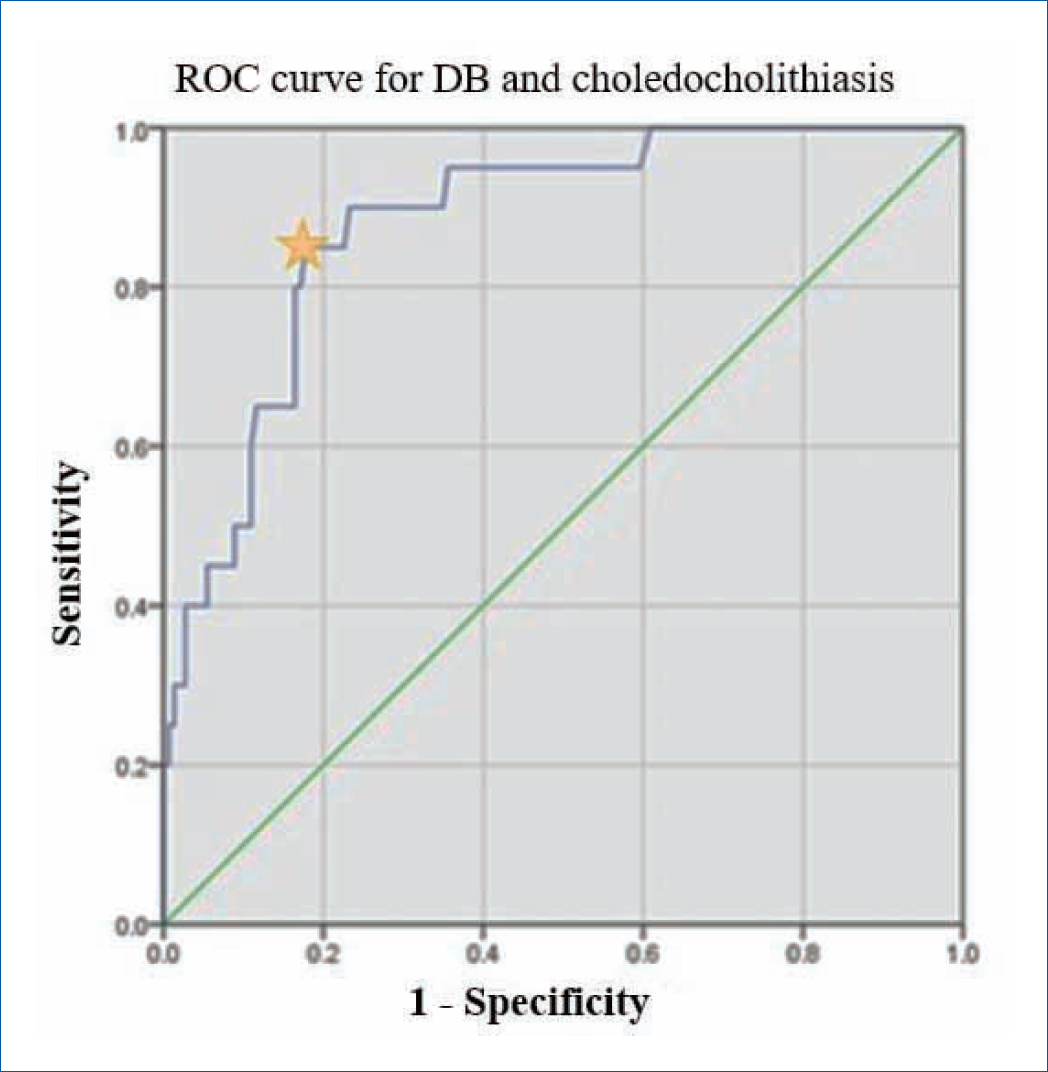

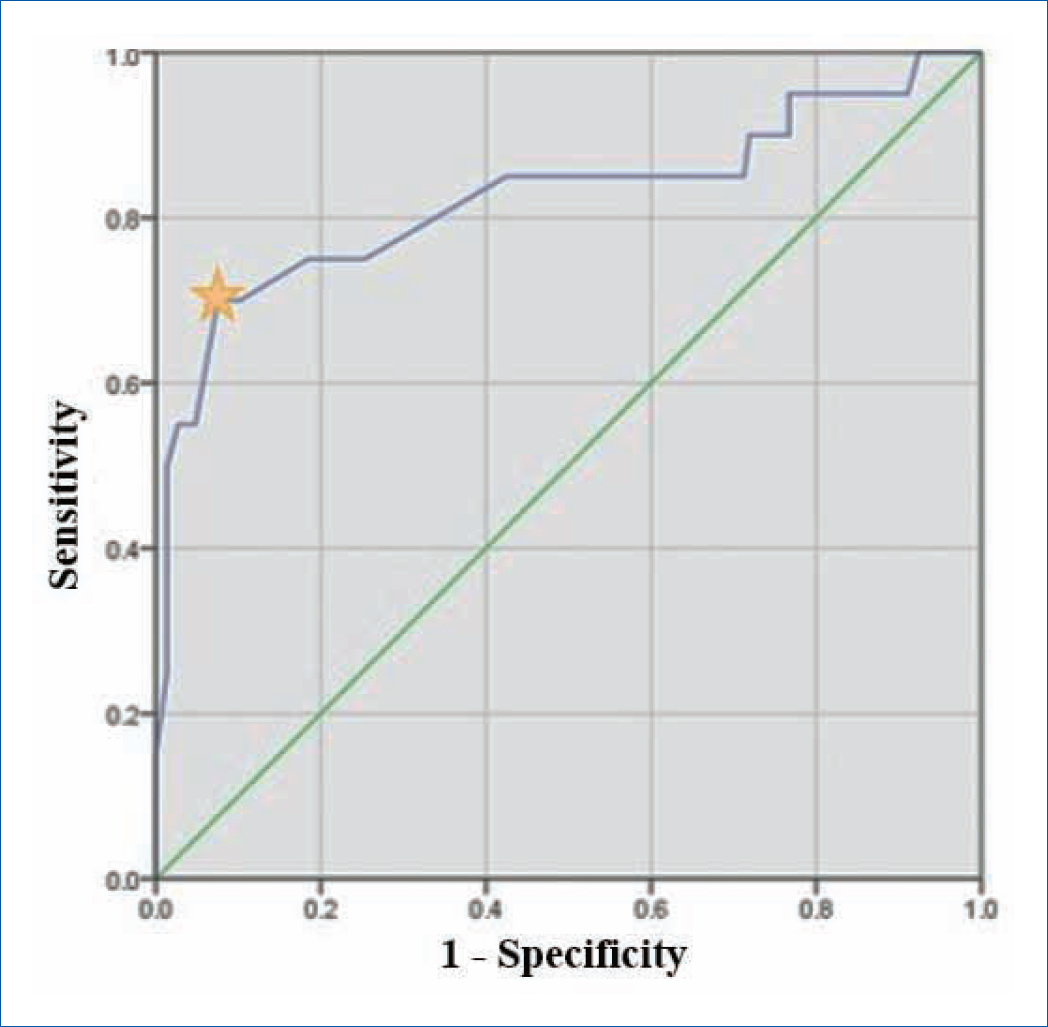

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves showed that the optimal cut-off points for DB and CBD diameter were 1.08 mg/dL (p < 0.001, AUC = 0.880) and 6.8 mm (p < 0.001, AUC = 0.824), respectively, for the presence of choledocholithiasis (Figs. 1 and 2). When variables were dichotomized at the new cut-off points, DB ≥ 1.08 mg/dL had the highest SE (85%) and NPV (97%) for the presence of choledocholithiasis, while the combination of DB ≥ 1.08 mg/dL and CBD diameter ≥ 6.8 mm had the highest SP (99%) and PPV (91%) (Table 4).

Figure 1. ROC curve for DB and choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC; AUC: 0.880; p ≤ 0.001; *value: 1.08; SE: 85%; SP: 83%.

Figure 2. ROC curve for CBD diameter and choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC; AUC: 0.824; p ≤ 0.001; *value: 6.8; SE: 70%; SP: 93%.

Table 4. Tests of diagnostic validity of new cut-off points for the detection of choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC

| Variable | SE | SP | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB > 1.08 mg/dL | 85% | 83% | 39% | 97% |

| CBD diameter > 6.8 mm | 70% | 92% | 56% | 95% |

| DB > 1.08 mg/dL + CBD diameter > 6.8 mm | 55% | 99% | 91% | 94% |

|

CBD: common bile duct; DB: direct bilirubin; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; SE: sensitivity; SP: specificity. |

||||

Discussion

MS Padda et al. found that patients with ACC and choledocholithiasis had the highest levels of LFTs compared to those without choledocholithiasis, ALP being the most affected altered in up to 77% of cases, followed by TB, which was elevated in 60% of cases13. Similarly, Videhult et al. showed an incidence of 42% of choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC and elevated LFTs, ALP and TB being the most reliable LFTs for detecting stones in the CBD14.

In the search for the ideal cut-off point of LFTs for detecting choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC, Chen et al. observed a SE of 100% and SP of 92% for a cut-off point of 0.9 mg/dL in the DB for the detection of choledocholithiasis15. Meanwhile, Ahn et al. described GGT as the most reliable serological test for predicting the presence of choledocholithiasis, with a SE of 80% and SP of 75.3% for a cut-off point of 224 IU/L16.

In our study, a cut-off point of 1.08 mg/dL in the DB was obtained as the most significant serological test in the detection of choledocholithiasis in patients with ACC, with a SE of 85%. Thus, the great usefulness of DB in clinical practice is found in its power to rule out the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis when a value of less than 1.08 mg/dL is found, thanks to its high NPV of 97%. On the other hand, the combination of this DB greater than 1.08 mg/dL and CBD diameter bigger than 6.8 mm achieved a SE of 99% and PPV of 91%, integrating a high diagnostic power for the detection of choledocholithiasis.

Conclusion

A DB greater than 1.08 mg/dL is the most useful test to begin suspecting choledocholithiasis, with a SE of 85%, and patients who would benefit from some specialized imaging study of the biliary tract. Meanwhile, a result lower than this gives us the highest probability of not having choledocholithiasis, with an NPV of 97%, and patients who can proceed to cholecystectomy without additional imaging studies.

On the other hand, the combination of DB greater than 1.08 mg/dL and a CBD diameter greater than 6.8 mm is the most useful parameter to confirm the presence of choledocholithiasis, with an SP of 99% and PPV of 91%, patients who would benefit from direct ERCP.

In general, none of the LFTs alone represents a reliable method to identify stones in the biliary tract, so their combination with a dilated CBD diameter is necessary for high suspicion of choledocholithiasis. However, there is a possibility of omitting a specialized study of the biliary tract and proceeding directly to cholecystectomy safely in patients with a DB lower than 1.08 mg/dL and a normal CBD diameter with a low possibility of choledocholithiasis.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Use of artificial intelligence for generating text. The authors declare that they have not used any type of generative artificial intelligence for the writing of this manuscript, nor for the creation of images, graphics, tables, or their corresponding captions.