Introduction

The most common childhood cancer worldwide is leukemia, with the highest percentage belonging to acute lymphoblastic leukemia¹. It is triggered by the proliferation and malignant transformation of immature lymphoid progenitor cells in the bone marrow, blood, and extramedullary sites1–3.

It typically appears between the ages of 2 and 6 but can also affect adults, where treatment is more challenging. The disease shows a 1.3:1 female-to-male predominance2. Diagnosis requires the presence of 20% or more lymphoblasts in the bone marrow or peripheral blood3,4. At the time of diagnosis, 5% up to 8% of patients present with central nervous system (CNS) involvement, often with cranial nerve abnormalities or meningism³. It can also lead to anemia, liver and kidney failure, and damage to other organs5.

The therapeutic approach is similar in both children and adults and should start immediately upon diagnosis4–6. Available treatments aim to control the bone marrow and systemic disease, particularly in the CNS7. These treatments are primarily chemotherapy-based and administered orally, IV, or intrathecally6. They are categorized into induction, consolidation, and long-term maintenance therapies4. The first phase, called “induction,” aims to achieve remission at the early stage of the disease; those who do not respond have a poor prognosis8. The second phase, “consolidation,” eliminates residual leukemic cells after the first phase. The third and final phase, “maintenance,” aims to prevent relapse and extend remission4.

Triple intrathecal chemotherapy involves administering 3 combined agents (methotrexate, cytarabine, and a glucocorticoid) to synergize the prophylactic and remedial effects in cases of CNS leukemic involvement7,8. Administration is performed via direct injection into the CNS to reach therapeutic concentrations by crossing the blood-brain barrier7.

Minimal or moderate sedation, or sedoanalgesia, is considered an anesthetic technique to provide anxiolysis, analgesia, and immobility for pediatric oncohematologic patients, optimizing the conditions for the procedure9. Intrathecal treatment is safe and effective, even in areas outside the operating room10. Although sedation levels vary based on the children’s needs, agents capable of causing deep sedation with rapid recovery are preferred9.

Balanced sedation uses more than 1 anesthetic, sedative, or analgesic agent in proportions that guarantee anxiolysis, sedation, analgesia, and amnesia10. In pediatric patients, ketamine and propofol are primarily used, inducing deeper sedation. Higher proportions of ketamine increase the likelihood of side effects9. Propofol is associated with fewer adverse effects and a short recovery period11. Nonetheless, the safety of sedation in pediatric patients is not guaranteed, and adverse events may occur even 2 hours after the intervention9.

The objective of this study is to identify the incidence of side effects in children on intrathecal chemotherapy.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a descriptive, retrospective, and cross-sectional study.

Study population

The study included a total of 51 pediatric oncohematologic patients diagnosed with acute or chronic lymphoblastic leukemia at a tertiary referral center of the Mexican Social Security Institute in Puebla, Mexico.

Inclusion criteria were patients aged 4 up to 18 years on intrathecal chemotherapy, categorized as ASA III, of any sex, with informed assent -for those aged 8 or older- and informed consent from their parents or guardians. Exclusion criteria included patients with a history of allergy or contraindication to any IV or inhaled anesthetic and those presenting with fever, epistaxis, or respiratory symptoms at the beginning of the procedure. Patients who voluntarily withdrew from the study were also excluded.

Variables and measurements

Variables evaluated included age, sex, premedication for nausea/vomiting/pain, intra-anesthetic time, recovery time, post-anesthetic nausea, vomiting, and pain, and the anesthetic technique used (balanced sedoanalgesia or IV sedoanalgesia). Drugs used and the presence of intra-anesthetic complications were recorded, along with anesthetic recovery time. Post-anesthetic side effects were monitored up to 1 hour after leaving the operating room.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics. Differences in anesthetic techniques and major side effects were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test, while intra-anesthetic time and recovery time were analyzed using Student’s t-test. Data were processed with GraphPad Prism 8 software.

Ethical considerations

This study was authorized by the IMSS Local Health Research Committee No. 2101. Participants signed informed consent forms, and their anonymity was maintained throughout the study. Patient information was used strictly for the purposes of this study.

Results

A total of 51 patients were included, 33 men (64.7%) and 18 women (35.3%), with ages ranging from 4 up to 15 years and 11 months (mean: 10.25; standard deviation: 3.88). Two anesthetic techniques were used: IV sedoanalgesia (n = 16) and balanced sedoanalgesia (n = 35).

A history of post-anesthetic emesis prompted premedication in 18 patients. Emesis occurred in 6 patients, associated with early intake of beverages or food due to irritability, but without statistical significance (p = 0.1750) (Table 1). No significant differences were found in postoperative pain between patients with and without analgesic premedication (Table 1).

Table 1. Side effects of analgesic and antiemetic premedication

| Side effects | Premedication for nausea | p | Premedication for pain | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Nausea | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) | 0.0782 | 0 (0%) | 14 (100%) | 0.1704 |

| Vomiting | 1 (5.5%) | 17 (94.5%) | 0.1750 | 1 (7.1%) | 13 (92.9%) | 0.2745 |

| Headache | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) | > 0.9999 | 1 (7.1%) | 13 (92.9%) | 0.2745 |

| Pain | 0 (0%) | 18 (100%) | > 0.9999 | 0 (0%) | 14 (100%) | 0.9999 |

| None | 17 (94.5%) | 1 (94.5%) | 0.1314 | 12 (85.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | > 0.9999 |

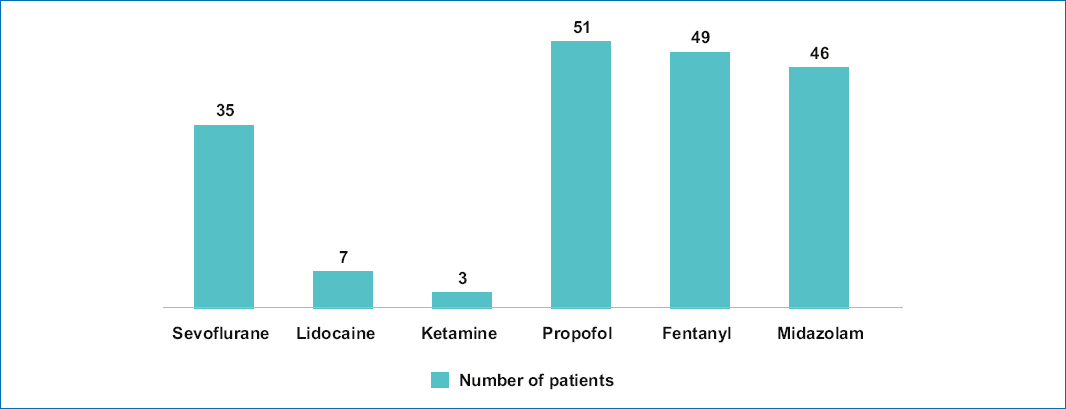

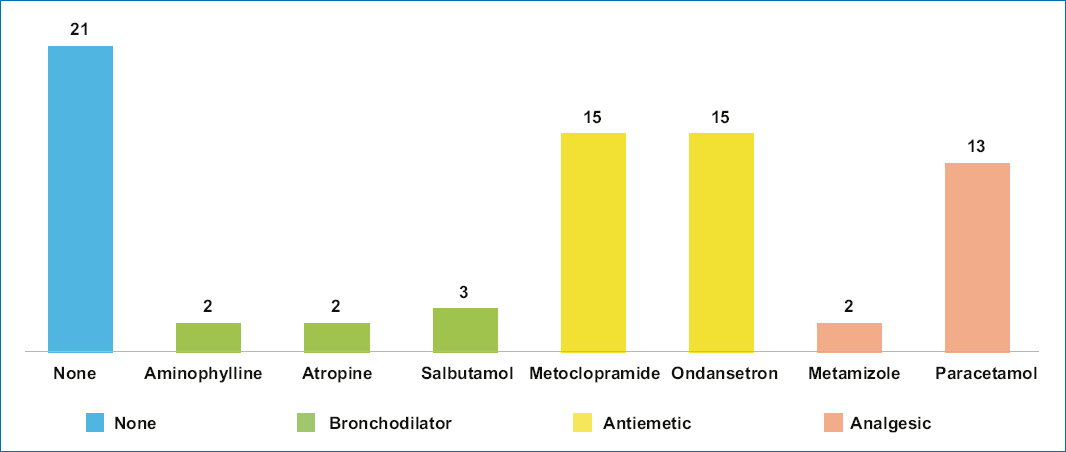

The most widely used drugs for sedoanalgesia were propofol (51 patients, 100%), fentanyl (49 patients, 96%), and midazolam (46 patients, 90.1%) (Fig. 1). The most widely used premedication drugs were ondansetron (15 patients, 29.4%) and acetaminophen (13 patients, 25.4%) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Most widely used drugs to induce anesthesia in pediatric patients.

Figure 2. Drugs used to prevent nausea and vomiting in the postoperative period and for analgesic management in pediatric patients.

The mean duration of the intra-anesthetic period in patients premedicated for pain was 22.1 minutes (18.3 minutes in non-premedicated patients [p = 0.0373]). Differences in recovery time were not significant (mean 27.86 vs. 25.5 min, respectively; p = 0.2839).

Patients premedicated for nausea had longer average intra-anesthetic periods (22.7 min) vs non-premedicated patients (17.5 min) (p = 0.0015). Recovery room stay was similar in both groups, with a mean time of 25.3 minutes in the premedicated group and 24.3 minutes in the non-premedicated group (p = 0.6965). Finally, recovery room stay in relation to the anesthetic technique showed that patients who underwent balanced sedoanalgesia stayed a mean 29.1 minutes, which is longer than those with IV sedoanalgesia (mean: 22.5 min) (p = 0.001).

Discussion

The present study was conducted to detect the occurrence of sedoanalgesia-related adverse effects in the administration of intrathecal therapy in pediatric patients with oncohematological diagnoses.

The tertiary referral center of the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) in Puebla, where this study was conducted, provides services to a high percentage of cancer patients. The implementation of the OncoCREAN model (State Reference Center for the care of children with cancer) facilitates access for pediatric cancer patients to specialized medical services close to their place of origin. Within this framework, knowledge of 3 fundamental pillars is imperative: outpatient invasive procedures, anesthetic management of pediatric oncohematological patients, and the incidence of post-anesthetic side effects¹².

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common pediatric malignancy, occurring when the body produces an excess of a type of white blood cell (lymphoblasts), damaging B and T lymphocytes5. It accounts for 75% up to 80% of acute malignant diseases in childhood3. In this study, with 51 patients, the mean age was 10 years. The incidence rate of ALL in children younger than 15 years is 3 to 4 cases per 100,000 children3. It is considered the largest diagnostic group among survivors of childhood malignancies13.

All phases of treatment (induction, remission, consolidation, and maintenance) aim to prevent and destroy leukemia cells that have spread to other areas, including the brain and spinal cord14,15. In this study, 100% of the patients showed signs of dissemination, indicating the need for intrathecal chemotherapy. This chemotherapy is administered directly into the cerebrospinal fluid in the presence of CNS dissemination7,16; the most effective technique for its administration is lumbar puncture9. This procedure is crucial in the pediatric population for diagnosing CNS dissemination and later for treatment, assisting in patient follow-up according to an individualized protocol9. Intrathecal chemotherapy used to treat ALL achieves high cure rates, especially in children, although unfortunately, it does not have the same outcome in adults4.

For children on intrathecal chemotherapy, sedation is essential to reduce anxiety and pain17. It is a misconception that pediatric patients do not experience pain or respond to painful stimuli in the same degree as adults18,19. Pain management in pediatric populations requires more supportive care than in adults20. Sedation should optimize the tolerability and successful completion of the procedure by avoiding pain and patient awareness²¹. The ideal anesthetic should allow for a painless procedure, be cost-effective, have no anesthetic or local complications, or cause stress to either the patient or the physician22. This study aims to identify the drugs that come closest to the ideal anesthetic.

The anesthetic technique was individualized according to each patient’s needs, and the option that, according to the literature, provided the most safety and efficacy was evaluated22. Propofol was the most frequently used drug in this population (100%), which is consistent with international literature23. It provides a rapid onset of action (approximately 30 seconds) and typically quick recovery24, with no demonstrated incidence of adverse effects linked causally24.

In pediatric populations exposed to sedation, there is a possibility of developing long-term side effects17. Factors such as the treatment phase, age, previous complications from the underlying condition, cancer history, and the need for anxiolytic, antiemetic, or analgesic premedication can help maximize the anesthetic procedure and reduce or even avoid side effects.

The findings from this study were significant. In contrast to international reports, the incidence of nausea or vomiting was low (only 18.3%, all without antiemetic premedication) and was related to the early intake of liquids and food due to irritability. Pain occurred in 2 patients at the puncture site due to multiple dural punctures (2 attempts). In one patient, the pain persisted with a score of 4/10 on the numeric pain scale for 2 hours, requiring analgesic medication after intrathecal chemotherapy administration. The other patient who reported pain was evaluated using the facial pain scale and scored 3 (mild/moderate pain), requiring trans-anesthetic analgesic management and subsequent pain improvement to 0 after 1 hour after surgery.

This study sought to assess the relationship of side effects between different anesthetic techniques. It is crucial to consider that the correct application of the anesthetic technique is necessary for this type of procedure21. It was reported that balanced sedoanalgesia resulted in longer trans-anesthetic times (IV sedoanalgesia: 21.2 min vs balanced sedoanalgesia: 24.3 min) and longer post-anesthetic care unit stays (IV sedoanalgesia: 22.5 min vs balanced sedoanalgesia: 29.1 min).

Conclusions

Although nausea is the most common post-anesthetic side effect, it is not statistically significant. Pain was present in a minimal percentage of patients. In contrast to international reports, a low incidence of post-anesthetic side effects was observed.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Use of artificial intelligence for generating text. The authors declare that they have not used any type of generative artificial intelligence for the writing of this manuscript, nor for the creation of images, graphics, tables, or their corresponding captions.